Contents

Dolmens of the Levant - an overview

Dolmens are mysterious megalithic structures found in landscapes ranging from the British Isles to Japan and Korea, and to the Horn of Africa. The majority of dolmens outside the Levant date to the local Neolithic cultures (Roughly if possible mention the years), yet it is difficult to determine not only when but also why people of diverse cultural entities built them. Dolmens vary in shape, size, rock type, stonemasonry, and architectural design, and many attempts have been made to describe and classify their structural variety. Dolmens typically consist of a single chamber built of standing walls and roofed by one or more large capstones. In many cases, but clearly not in all, the chamber is set in a stone pile called a tumulus or cairn, which may be surrounded by an outer wall.

Dolmens are found in the Levant from Turkey to Egypt and east into the Arabian Desert. After more than 100 years of their study, nearly all aspects remain the subject of debate, including construction technique, morphological typology, function and, primarily, their date of construction. Confounding research efforts is the fact that dolmens, visible and rather pronounced in the Levantine landscape, have been robbed and reused throughout the region’s history. Moreover, dolmens did not receive appropriate attention by most archaeologists for many reasons, mostly practical. The majority of dolmens are located in rural areas, mountain foothills, and rocky terrain, largely overlooked by development and major archaeological enterprises. Here we define a (Levantine) dolmen as a megalithic burial structure constructed from unhewn mega-stones with no cementation between them

Rock Art in Levantine Dolmens

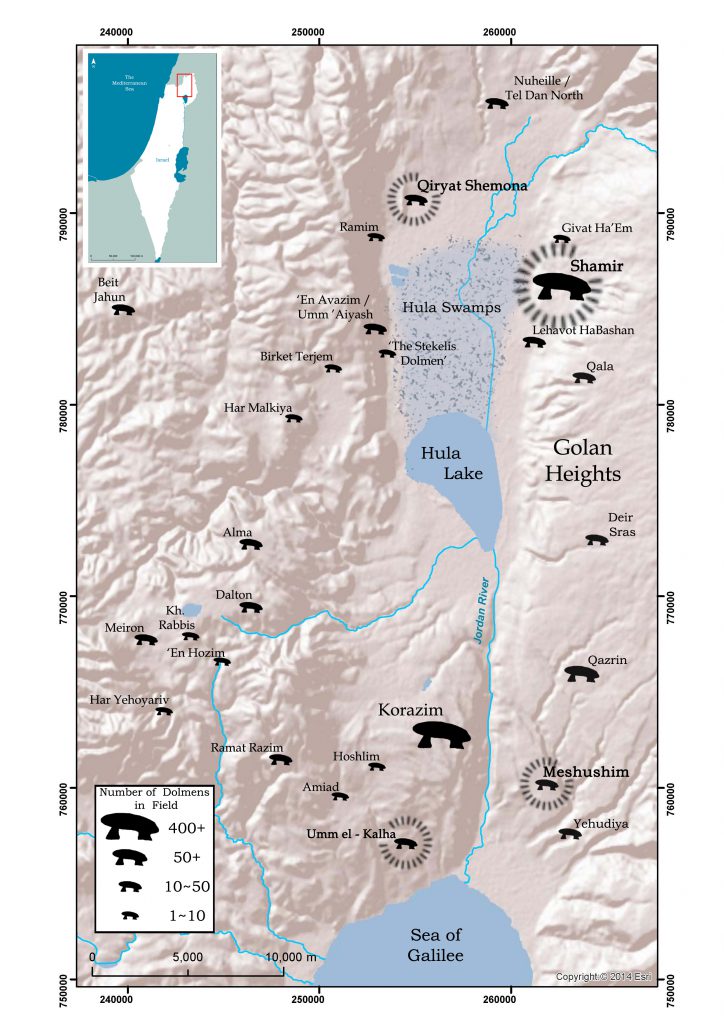

Thousands of dolmens are scattered throughout the southern Levant, mainly in Syria, Israel, and Jordan. These megalithic burials,

dated to the early stages of the Bronze Age, are an understudied and little understood phenomenon of Levantine archaeology.

Unlike in Europe and other parts of the world, rock art has rarely been reported from Levantine dolmens, despite more than

150 years of research and hundreds of excavated dolmens of the thousands of megalithic structures recorded. A fortunate

discovery, in 2012, of engraved features on the ceiling of the central burial chamber of a giant dolmen in the Shamir Dolmen

Field has markedly altered our current body of knowledge. Since this finding, rock art has been discovered at three additional

dolmen sites. These latest discoveries are presented in the context of their significance to the broader phenomenon of the

mysterious megalithic burials of the Levant.

Published in

Sharon, G., Berger, U., 2020. Rock Art in South Levantine Dolmens. Asian Archaeology. 4, 17–29.

Lehavot Habashan Dolmens

On the low escarpment of the Golan north of Kibbutz Lehavot Habashan are two small, simple trilithon type dolmens (Figs. 1 and 2). The dolmens were built on the western slope of a basalt hill, a basalt flow with an escarpment facing west and south of the inflow of the Orvim Canyon to the valley (coordinates 261328:783437).

These dolmens could possibly be the very southern margin of the large Shamir Dolmen Field to the north (see below). Many additional structures are visible in the vicinity, indicating the presence of a group of dolmens that a systematic survey can confirm. Dolmen LHB-1 is a small trilithon built on an east-west axis. The capstone

is 150×90×40 cm in size. The second dolmen, LHB-2, is somewhat larger and built on a north-south axis. One large stone was used for the west wall and the hillside (in place of a stone) for the east wall, with the eastern portion of the capstone resting on small stones on the slope to create the dolmen chamber. The irregular shaped

capstone is 220×160×60 cm in size.

Royal Dolmens of the Nukheile

A vast field of basalt dolmens and additional stone structures spreads eastward from the Hasbani Stream to the foothills of the Hermon Mountain. The dolmens in this field were first discovered in spring 1882, when Prince Albert Victor and his younger brother, prince George (later King George V) toured the Holy Land guided by C. R. Conder of the PEF. Walking the route from the Upper Galilee to Tel Dan, the royal party discovered and documented four basalt dolmens. Their discovery was described as a highlight of the three-year, royal worldwide cruise . For 130 years, this report has remained the primary source for our knowledge of the Nuheille Dolmens (Fraser 2018; Hartal 1987). In more recent history, this region was located on the border between the French and British mandates and since 1949 between Syria, Lebanon, and Israel, inaccessible for decades and nearly forgotten.

In the spring of 2016, the Berger & Sharon conducted a survey in the footsteps of the royal delegation in an attempt to find the dolmens. Twenty-four dolmens and numerous additional stone structures were documented in this heavily disturbed region. The area has been subject to damage by military activity, development (including the laying of the `Tapline` oil pipeline between Iraq and the Lebanese shores), and agricultural activity. The actual dolmens described in Conder’s report were finally identified in the summer of 2018 (Prince Albert Victor and Prince George of Wales 1886).

Shamir Dolmens Field

The largest and most significant dolmen concentration in the Hula Valley surrounds (and is inside) Kibbutz Shamir. M. Kagan and Stekelis surveyed more than 400 dolmens on the basalt steps slanting westward from the Golan . The pre-1967 Syria-Israel international border runs through the dolmen field, preventing the survey of its eastern section at the time. During the six decades since its discovery, 13 dolmens have been excavated in the Shamir Dolmen Field, primarily as part of a salvage excavation following kibbutz development (Bahat 1972; Sharon et al. 2017; Zingboym 2009, 2011).

The Shamir Dolmen Field extends over a few square kilometers of Middle Pleistocene Age basalt flows. The flows formed into a series of very large slabs and giant boulders, few meters in size and the landscape is of steps (probably of tectonic origin) slanting westward into the Hula Valley, some 150 m below. These giant slabs were the ideal raw material for dolmen construction. Many of the dolmens were built directly on the slopes, simplifying transport of the giant stones. Yet, numerous dolmens were also built on the plateaus between and above the slopes, meaning that the giant rocks were carried uphill a considerable distance to their final position. While many types of dolmens can be identified in Shamir, an overall architectural line can be observed. The Shamir Dolmen Field includes most dolmen types, at times scattered within a few meters of one another. Yet, the most distinct type of Shamir dolmen is a circular tumulus, built around a large central chamber entered through a vestibule and covered with a giant capstone. Each of the massive capstones in the Shamir Dolmen Field rises out of its tumulus, most likely designed by the dolmen builders as a prominent landmark, visible even today.

The fortunate discovery of rock art on the ceiling of the main chamber in Dolmen 3 prompted new research of the Shamir Dolmen Field . Four dolmens were excavated and mapping and surveys are ongoing. The results of the excavation at Dolmen 3 were reported elsewhere and will be summarized briefly here with preliminary observations from excavation of the other three dolmens at Shamir and the survey conducted.

Kiryat Shmona Face Dolmen

Few dolmens of the Qiryat Shemona North Field survived the development and construction. Among them is the largest dolmen reported of that field, located on the east facing margin of a low hill, overlooking the Hula Valley (Dolmen QSh-1; 254870/ 790860; Fig 9a, b). This dolmen is constructed of three upright large slabs forming a chamber 180 x 80 cm and covered by a single large capstone 200 × 200 × 40 cm in size. The chamber is surrounded by well-built stone wall c. 10 m in diameter. On the flat surface of one of the eastern stones of the surrounding wall, a board game was engraved in an unknown period. Possibly the most unique feature of Dolmen QSh-1 is the lines carved into the upper surface of the capstone. The location and nature of these marks suggest that they are not functional quarry features but rather were carved for a different reason. What appears to be the carving of a face in the stone points to the possibility of symbolic art; however, more study is needed before such suggestion can be substantiated.

Reference –

Sharon and Berger 2020 Rock art in Southern Levant Dolmens. Asian Archaeology 4. 17-29.

The Meshushim Rock Art Panel

The Nahal Meshushim (Hexagonal River) dolmen is a large, single megalithic structure standing atop a low hill overlooking the Sea of Galilee to the southwest (262,300/ 760185 ITM / N32.9358°, E035.6625° WGS 84).

Today, the dolmen is surrounded by the ruins of the Ottoman village Qal‘a el-Qara‘neh, currently part of the Meshushim Nature Reserve. It appears that the dolmen is a remnant of a vast dolmen field, spreading south and southwest on the western slopes of the Golan Heights along the eastern bank of the Jordan River canyon

Reference –

Sharon and Berger, 2020. Rock art in Southern Levant Dolmens. Asian Archaeology 4. 17-29.

Dir Saras Dolmens

Large dolmens field east of Gesher Benot Ya’aqov. Partly excavated by Clair Epstein. Surface finds – Bronze dagger & red bead