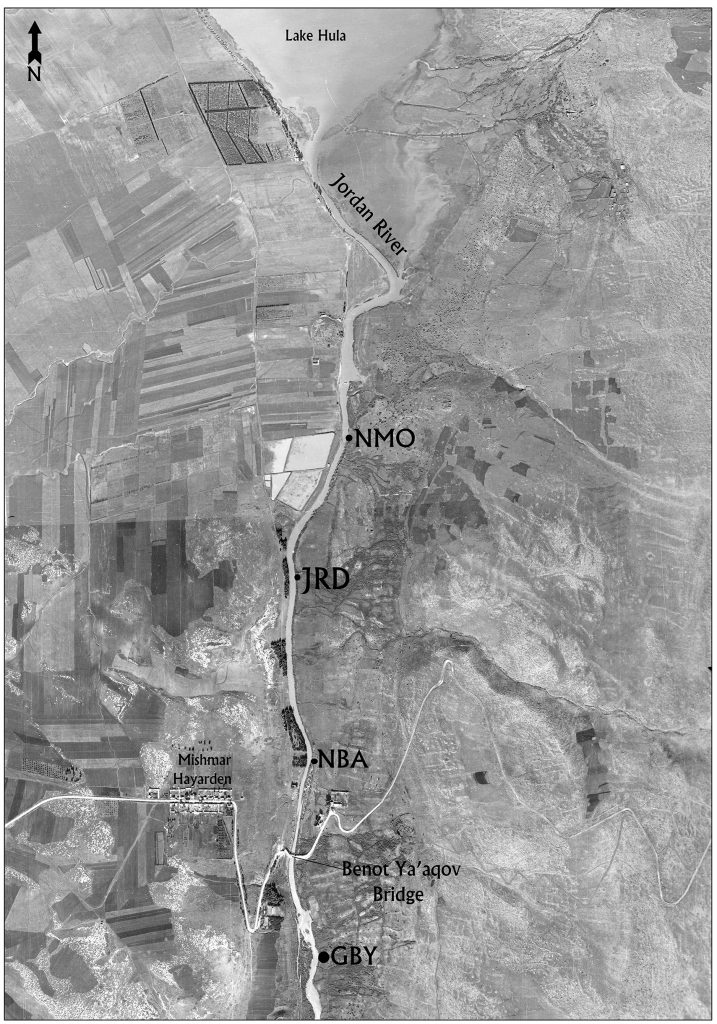

Prehistoric Upper Jordan River

On its course southward out of the Hula Valley the Jordan River exposes geological layers ranging in age from the Pliocene to the Holocene. A combination of volcanism, tectonic movements and nearly 200 years of drainage operations created a unique setting in which sediments over one million years old are visible on the banks of the river in close proximity to horizons laid by the last century’s Hula Lake.

Since the northern segment of the Dead Sea Rift has been flourishing with water, flora and fauna for at least the last one million years, it is not surprising that many of the exposed geological formations contain evidence of intensive human occupation of this region.

Alongside the broad exposure of archaeological bearing sediments, are uniquely well-preserved ancient flora specimens.

The sediments composing the banks of the Jordan River have been waterlogged since their accumulation. The result is a large assemblage of wood, bark, seeds and fruits holding unique information on the environment of the upper Dead Sea Rift during the Pleistocene and the behaviour and diet of early humans in this landscape.

The presence of prehistoric sites exposed on the banks of the Jordan River was discovered in the 1930s. Leading archaeologists such as Moshe Stekelis and David Gilead studied these sites during the earlier decades, while leading geologists described the highly complex stratigraphy of the region. Findings of the earliest evidence of human occupation in the immediate region, from the Acheulian site Gesher Benot Ya’aqov (GBY), ca. 750,000 BP, have been the focus of a more recent and on-going study led by Prof. N. Goren-Inbar of the Hebrew University.

The results of this research established GBY as one of the most significant Acheulian sites worldwide.

In the last decades, new excavations and studies have shown that adjacent to the important Early to Middle Pleistocene sites, the region also has younger sites with unique and significant information on human presence during the Late Pleistocene. These sites, dated to the Middle, Upper and EpiPaleolithic as well as to the Neolithic, place the GBY area as the chronologically longest and most complete stratigraphic sequence of human presence ever recorded in the Levant and possibly anywhere outside of Africa.

Furthermore, the location of the sites in the Northern Dead Sea Rift, which is the backbone of the Levantine Corridor and most commonly accepted as the primary path of human migration Out-of-Africa, makes the information retrieved from them highly significant to our understanding of the timing and spacing of human dispersal.

Upper Jordan River - 1945